1. OSTIA

I first came to Rome for Easter 1978. I travelled down from Turin with my boss, Sue, and my best friend, Charlie, in Sue’s Volkswagen Beetle. I sat in the back with Lucifero, Sue’s boxer, constantly scooping the drool from his jowls before he could shake his head. Italy was in a state of alert because the Christian Democrat leader, Aldo Moro, had been kidnapped, but what we didn’t know was that a bunch of foreigners from Turin was believed to be involved. We couldn’t understand why, at every road block, we were stopped by armed police. Each time, we were ordered out of the car and told to stand against it, hands on the roof, legs spread; each time, Lucifero would leap from seat to seat in a frenzy, sliming the windows and seats with mucus, while Sue explained once again that her personal and car documents were in her other handbag, the one she’d left on the kitchen table in Turin; each time, her charm and hilariously bad Italian saved us, just, from arrest.

When we finally reached the ring road surrounding Rome, Sue decided we should find a hotel outside the centre, where Lucifero would be welcome. We drove to Ostia, the setting for scenes from some of Pasolini’s grittily realistic films and, the year before our visit, his grittily realistic death. The only hotel with vacancies was a stuccoed beige block with a chilly veranda-cum-dining room attached to the front. The rooms were bare, uninviting, damp. This looks fine, said Sue, who’d promised to pay. After we’d heaved her enormous suitcase onto her bed, Charlie and I mooned along the beach, taking photographs of chipped blue-painted changing cubicles and boarded-up bars while Sue unpacked, Lucifero barking frantically at the cold grey sea.

When we finally reached the ring road surrounding Rome, Sue decided we should find a hotel outside the centre, where Lucifero would be welcome. We drove to Ostia, the setting for scenes from some of Pasolini’s grittily realistic films and, the year before our visit, his grittily realistic death. The only hotel with vacancies was a stuccoed beige block with a chilly veranda-cum-dining room attached to the front. The rooms were bare, uninviting, damp. This looks fine, said Sue, who’d promised to pay. After we’d heaved her enormous suitcase onto her bed, Charlie and I mooned along the beach, taking photographs of chipped blue-painted changing cubicles and boarded-up bars while Sue unpacked, Lucifero barking frantically at the cold grey sea.

We were stopped three more times by police on the drive from Ostia to Rome. The third time, we leapt from the car and adopted the position without being told, arousing further suspicion. It took us almost an hour to convince them we were genuine tourists. Later, driving beneath the flickering arch of maritime pines along the Via del Mare, Sue’s patience snapped. She had to get her hair done, she said. The plan was to go to the Vatican, we reminded her. ‘I think I’ve already been,’ she said. She double-parked outside a parrucchiera that also offered manicures. ‘I’ll meet you here in three hours,’ she told us, then glanced down at the chipped red varnish on her toes. ‘Make that four.’

We ate that evening in a restaurant on the road to Ostia, two hundred yards from the catacombs and the Appian Way. The outer walls were encrusted with shards of pottery and scraps of Roman statuary. Inside, the place was empty. We stood by the door, Lucifero skulking at Sue’s heel. After a moment, muttering from behind a screen painted in Pompeii red was followed by what sounded like a thump. A waiter appeared in the breastplate and pleated miniskirt of a gladiator. When Sue began to giggle, the waiter froze, then turned to hiss at whoever was standing behind him. Eventually we were served. The food was dreadful, though we didn’t realise how dreadful at the time. We barely noticed what we ate as the restaurant filled with coach-loads of hungry pilgrims and what looked like the cast of Ben Hur passed by bearing plates of lukewarm pasta alla carbonara.

We ate that evening in a restaurant on the road to Ostia, two hundred yards from the catacombs and the Appian Way. The outer walls were encrusted with shards of pottery and scraps of Roman statuary. Inside, the place was empty. We stood by the door, Lucifero skulking at Sue’s heel. After a moment, muttering from behind a screen painted in Pompeii red was followed by what sounded like a thump. A waiter appeared in the breastplate and pleated miniskirt of a gladiator. When Sue began to giggle, the waiter froze, then turned to hiss at whoever was standing behind him. Eventually we were served. The food was dreadful, though we didn’t realise how dreadful at the time. We barely noticed what we ate as the restaurant filled with coach-loads of hungry pilgrims and what looked like the cast of Ben Hur passed by bearing plates of lukewarm pasta alla carbonara.

Five years later, I moved to Rome, to live and work at the university as a language teacher. Aldo Moro was dead by then, his putative assassins – neither foreigners nor from Turin – in jail. Charlie had found a flat on the outskirts of Paris. The last I heard of Sue she’d been involved in a horse-racing scam with her funeral director boyfriend and had moved on from Turin, but that may not have been true. Lucifero may have been dead. When summer arrived I began to go to the free beaches south of Ostia, taking the tube and then the bus, walking the last half-mile until I’d reached the strip known as the Buco, after the hole in the fence through which the first intrepid naturists had crawled before stripping off. The dunes were scattered with men, naked apart from the occasional floppy hat or knotted handkerchief, rising and falling on their heels like meerkats.

2. TERMINI

My first three months in Rome were spent in a cheap hotel near Termini station, in one of the hundreds of blocks designed to house the fledgling bourgeoisie of the newly united Italy. They still look grand enough from the first floor up, apart from the dusty neon signs for the kind of hotel I was staying in, but the ground floors have been taken over by shops selling Chinese-made cheap leather goods, jeans, local varieties of fast food; the odour of spit roast chicken and reheated pizza hangs grease-heavy in the air. My room was on the third floor, with off-white plaster moulding round three sides of the ceiling and half the central rose still intact, ornate and dusty, against the fourth; the single room neighbouring mine must have been its mirror image. I wasn’t allowed to eat there, and in any case didn’t want to; the mood was depressing enough without crumbs in the bed and leftover packets of salami squirrelled away in suitcases in case the cleaner found them.

I passed my days waiting for the phonogram from the Ministry of Education that would confirm my contract, wandering around the station and the surrounding area, then down Via Nazionale to the rest of the city. I spoke to almost no one other than waiters in restaurants and the harassed English professor responsible for my contract. Friends who knew Rome had recommended restaurants that were good or cheap, but never both. It didn’t take long to move from the first group to the second. Mario’s (aka the Poisoner) in Trastevere – where you could eat a plate of pasta with oil, garlic and chilli pepper for less than 40p – was a favourite. Just round the corner, in Piazza de’ Renzi, was da Augusto, a trattoria with paper tablecloths and Castelli Romani wine on tap, run by a grumpy old man – presumably Augusto – with a speech defect and an upwardly mobile son. The fourth time I went there, I’d spoken to no one for almost three days. When Grumpy flung the menu onto the table and snapped at me that the lamb was off, I burst into unexpected tears. He hugged me, once, and brought me wine and bread. I’ve never been more grateful to anyone in my life, though his tone didn’t change and I was never hugged again. At a party years later I bumped into his son, accompanied by a glamorous American model, and told him what his father had done. ‘È sempre stato uno stronzo per bene,’ his son said cheerfully. He’s always been a decent sort of shit.

I passed my days waiting for the phonogram from the Ministry of Education that would confirm my contract, wandering around the station and the surrounding area, then down Via Nazionale to the rest of the city. I spoke to almost no one other than waiters in restaurants and the harassed English professor responsible for my contract. Friends who knew Rome had recommended restaurants that were good or cheap, but never both. It didn’t take long to move from the first group to the second. Mario’s (aka the Poisoner) in Trastevere – where you could eat a plate of pasta with oil, garlic and chilli pepper for less than 40p – was a favourite. Just round the corner, in Piazza de’ Renzi, was da Augusto, a trattoria with paper tablecloths and Castelli Romani wine on tap, run by a grumpy old man – presumably Augusto – with a speech defect and an upwardly mobile son. The fourth time I went there, I’d spoken to no one for almost three days. When Grumpy flung the menu onto the table and snapped at me that the lamb was off, I burst into unexpected tears. He hugged me, once, and brought me wine and bread. I’ve never been more grateful to anyone in my life, though his tone didn’t change and I was never hugged again. At a party years later I bumped into his son, accompanied by a glamorous American model, and told him what his father had done. ‘È sempre stato uno stronzo per bene,’ his son said cheerfully. He’s always been a decent sort of shit.

By day, though, it was churches and ruins. Obsessed by the Pantheon, my favourite building, I passed hours beneath its perfect dome, hoping for rain so that I could watch it enter through the central hole and sparkle white-gold as it fell. One May, a year or two later, I happened to be there for Pentecost, when firemen empty sacks of rose petals through the hole in the dome, a practice that began when Rome was home of emperors, until the interior is rippled by red-reflected light, the ancient floor a scented carpet lifted by breeze. I stared at the Byzantine mosaics in Santa Prassede for hours. I did the Borromini trail, from Sant’Agnese to Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, learning about Baroque by stroking its warm curves with my hands.

By day, though, it was churches and ruins. Obsessed by the Pantheon, my favourite building, I passed hours beneath its perfect dome, hoping for rain so that I could watch it enter through the central hole and sparkle white-gold as it fell. One May, a year or two later, I happened to be there for Pentecost, when firemen empty sacks of rose petals through the hole in the dome, a practice that began when Rome was home of emperors, until the interior is rippled by red-reflected light, the ancient floor a scented carpet lifted by breeze. I stared at the Byzantine mosaics in Santa Prassede for hours. I did the Borromini trail, from Sant’Agnese to Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, learning about Baroque by stroking its warm curves with my hands.

But all roads led back to Termini. Most evenings I’d eat a slice of pizza and hang around the station, drinking amaro Averna while conscripted soldiers barely out of high school drifted from bar to bar until they were picked up, or called it a night. Piazza Repubblica used to have two porn cinemas, the Moderno and the Modernetto, their raison d’être to provide a roof for the oldest profession in the world. Military service was abandoned some years ago, the conscripts replaced by rent boys from Eastern Europe, the cinemas converted into a luxury hotel. The underworld of the station has been spruced up into the retail experience all major cities offer, with rail travel an optional extra. Even the hotels around the station look smarter than they did, although the front they present can be fragile. In January this year, two Romanian girls, working as prostitutes, were found with their throats cut in a hotel fifty yards from the one I stayed in over twenty years ago.

3. TESTACCIO

My first real Roman home was in Testaccio: home in the sense that I didn’t pay by the day. I’d started work at the university and one of the professors said that her daughter had a room I could use if I didn’t mind roughing it. I went round that afternoon. The flat was on the second floor of a 19th century block, with a trattoria opposite that sold Marino wine by the litre. The Protestant cemetery was down the road and Monte Testaccio, the heap of ancient rubble that gave the district its name, a few minutes’ walk away. Miranda showed me the room and I understood what her mother had meant. There was a metal-framed bed in one corner and a trestle table in another, a single straight-backed chair. I didn’t care; I had a wall against which to stack my books and a floor to dump my suitcase on. Best of all, I could use the kitchen.

My first real Roman home was in Testaccio: home in the sense that I didn’t pay by the day. I’d started work at the university and one of the professors said that her daughter had a room I could use if I didn’t mind roughing it. I went round that afternoon. The flat was on the second floor of a 19th century block, with a trattoria opposite that sold Marino wine by the litre. The Protestant cemetery was down the road and Monte Testaccio, the heap of ancient rubble that gave the district its name, a few minutes’ walk away. Miranda showed me the room and I understood what her mother had meant. There was a metal-framed bed in one corner and a trestle table in another, a single straight-backed chair. I didn’t care; I had a wall against which to stack my books and a floor to dump my suitcase on. Best of all, I could use the kitchen.

I soon settled into a routine. Cappuccino and cornetto for breakfast, a rosetta – the ubiquitous breast-shaped roll, complete with nipple – stuffed with ham for lunch. In the evening, I made myself pasta and tomato sauce and drank a litre of rough red wine from the trattoria, then went to my room in a drunken haze to work on a jigsaw I’d found in the flat. I ate with the professor’s daughter once or twice but she led what struck me as a curious half-life in her room, decorated with artwork by the man who designed the monster in Alien, and didn’t seem to want to be friends; didn’t seem to want me there at all.

One day, she introduced me to someone she must have thought I’d like, a gay teenager from one of the working-class areas in the city’s outskirts who dressed in a sissified punkish way. He was flirtatious and dismissive in more or less equal measure; I took an instant dislike to him. The next time I heard his voice, I closed myself in my room. I’d bought the poster of Salò, Pasolini’s last film, to hang on my otherwise bare wall. I curled beneath my only other significant purchase, a second-hand German army duvet, fully dressed, to read his Roman novels in Italian. I spent more of my first few months in the Rome of Pasolini than in the one outside my door. At weekends, friends came down from the north to visit and I’d become a tourist again, crossing the river to Trastevere, exploring the Porta Portese Sunday flea market, forgetting that I lived there and would be alone again on Monday.

I moved back to Testaccio four years later, with my partner, to a three-roomed flat overlooking the more elegant of its two squares: Piazza Santa Maria Liberatrice, the one with the local church and the working theatre, rather than the smaller one round the corner where the food market was, although it’s since been moved. We had a flat on the top floor, our windows more or less level with the tops of the maritime pines rising from the gardens below. Our building was next to the one in which Gabriella Ferri, the Roman folk singer, had been born; there was great excitement when RAI television came to film her in the entrance, not long before she killed herself. A friend of mine bumped into her once in the Alibi, the gay club carved into the side of Monte Testaccio. She asked him if he had a joint, then drifted off, majestic and blonde and lost, before he had a chance to answer. More recently, Nicole Kidman pretended to be a Roman housewife on its roof terrace, pinning out her washing for an advertisement.

I moved back to Testaccio four years later, with my partner, to a three-roomed flat overlooking the more elegant of its two squares: Piazza Santa Maria Liberatrice, the one with the local church and the working theatre, rather than the smaller one round the corner where the food market was, although it’s since been moved. We had a flat on the top floor, our windows more or less level with the tops of the maritime pines rising from the gardens below. Our building was next to the one in which Gabriella Ferri, the Roman folk singer, had been born; there was great excitement when RAI television came to film her in the entrance, not long before she killed herself. A friend of mine bumped into her once in the Alibi, the gay club carved into the side of Monte Testaccio. She asked him if he had a joint, then drifted off, majestic and blonde and lost, before he had a chance to answer. More recently, Nicole Kidman pretended to be a Roman housewife on its roof terrace, pinning out her washing for an advertisement.

Testaccio’s proud of its reputation as the working class heart of Rome, though there’s increasingly little evidence of this apart from an atavistic attachment to Roma football club. The area’s part of the grown-ups’ playground of eating and drinking places that has taken over much of the centre since retail licensing was deregulated in Italy, not, surprisingly, by one of Berlusconi’s governments but by a centre-left administration. The change in the law went almost unnoticed but it’s as done as much as anything to destroy the sense Rome once gave of being a city of semi-autonomous quarters, each with its network of local shops . You could live in Piazza Navona thirty years ago and find practically everything you needed – from olive oil to knitting needles – without leaving the square. Now all you can do is eat, expensively, and drink coffee, and be a tourist.

4. CENTRO STORICO

I finally made it to the historic centre in my fourth year in Rome, moving into a shabbily splendid flat in Piazza Santa Caterina della Rota, the martyred virgin and founder, albeit unwillingly, of the Catherine wheel, just round the corner from Piazza Farnese, opposite the English College. I shared four hundred square metres – the entire second floor, the one above the piano nobile traditionally reserved for the building’s owners – with an English colleague and an American woman. The British Embassy had rented the place for its lowlier diplomatic staff, but it had fallen into my colleague’s hands and we lived there with remnants of its past, two broken-down but comfortable sofas, a dining table that would happily seat twenty, Murano chandeliers dangling imposingly from most of the ceilings, a kitchen only servants could be expected to work in, two poky bathrooms fitted in anyhow, as an afterthought or concession to mere bodily needs. The doors and ceilings were decorated with painted curls and floral business, lovelier for being faded. It was all I could do to sleep, my bed beneath a meringue of glass and pastel wreaths. Beneath my bedroom window was one of the few remaining petrol pumps in the city centre, and a bicycle shop. Their metal shutters, pushed noisily home, woke me each weekday morning at eight o’clock. With my windows thrown open, I could hear the seminarians in the street below as they bitched about one another or the older priests in their shrill camp voices, imagining themselves unheard. In the echoing high-ceilinged rooms, the three of us lived our separate lives as though we’d been billeted there in wartime and the owners had carried off what they could before the barbarians arrived.

I finally made it to the historic centre in my fourth year in Rome, moving into a shabbily splendid flat in Piazza Santa Caterina della Rota, the martyred virgin and founder, albeit unwillingly, of the Catherine wheel, just round the corner from Piazza Farnese, opposite the English College. I shared four hundred square metres – the entire second floor, the one above the piano nobile traditionally reserved for the building’s owners – with an English colleague and an American woman. The British Embassy had rented the place for its lowlier diplomatic staff, but it had fallen into my colleague’s hands and we lived there with remnants of its past, two broken-down but comfortable sofas, a dining table that would happily seat twenty, Murano chandeliers dangling imposingly from most of the ceilings, a kitchen only servants could be expected to work in, two poky bathrooms fitted in anyhow, as an afterthought or concession to mere bodily needs. The doors and ceilings were decorated with painted curls and floral business, lovelier for being faded. It was all I could do to sleep, my bed beneath a meringue of glass and pastel wreaths. Beneath my bedroom window was one of the few remaining petrol pumps in the city centre, and a bicycle shop. Their metal shutters, pushed noisily home, woke me each weekday morning at eight o’clock. With my windows thrown open, I could hear the seminarians in the street below as they bitched about one another or the older priests in their shrill camp voices, imagining themselves unheard. In the echoing high-ceilinged rooms, the three of us lived our separate lives as though we’d been billeted there in wartime and the owners had carried off what they could before the barbarians arrived.

5. SAN LORENZO

I first lived in San Lorenzo when we moved back to Rome in 1991 after a failed attempt to relocate in London, but the district had always been on my personal map of the city since I was first taken to da Franco, a fish restaurant in Via dei Falisci, famous for being cheap, generous with its portions and not a risk to health. Residential San Lorenzo is wedged into a sort of quadrilateral, with Termini and the city’s historic cemetery, Verano, roughly to its west and east, while to the south lies Scalo di San Lorenzo, a square kilometre or so of railway lines representing the main transport hub of the capital and the reason the district was bombed more heavily than any other during World War Two; the scars can still be seen. Like Testaccio, it was predominantly working class; unlike Testaccio, it still is, although the proximity of Rome’s main university, La Sapienza, to the north of the area, has led to an influx of students, sharing rooms in hastily converted, over-priced apartments and enlivening the early hours in a variety of bars and pizzerias, much to the chagrin of those historic residents who haven’t let their homes and loved somewhere quieter.

I first lived in San Lorenzo when we moved back to Rome in 1991 after a failed attempt to relocate in London, but the district had always been on my personal map of the city since I was first taken to da Franco, a fish restaurant in Via dei Falisci, famous for being cheap, generous with its portions and not a risk to health. Residential San Lorenzo is wedged into a sort of quadrilateral, with Termini and the city’s historic cemetery, Verano, roughly to its west and east, while to the south lies Scalo di San Lorenzo, a square kilometre or so of railway lines representing the main transport hub of the capital and the reason the district was bombed more heavily than any other during World War Two; the scars can still be seen. Like Testaccio, it was predominantly working class; unlike Testaccio, it still is, although the proximity of Rome’s main university, La Sapienza, to the north of the area, has led to an influx of students, sharing rooms in hastily converted, over-priced apartments and enlivening the early hours in a variety of bars and pizzerias, much to the chagrin of those historic residents who haven’t let their homes and loved somewhere quieter.

Eleven years after that first plate of spaghetti alle vongole I found myself living three streets away and then, a few months later, almost directly opposite da Franco. The flat was tiny, but we were grateful to be back in Rome and to have what passed for a terrace, overlooked on all sides by taller buildings with external balconies and occasionally used as a bin for cigarette ends, scraps of paper, sweet wrappers and used condoms, which we would sweep up every few days. We stayed there for a few years, making friends with our neighbours in the other three flats in the building and becoming regulars at Bar Marani, a bar whose clientele covered the entire demographic of the quarter, from creative types, impecunious and otherwise, to signore of a certain age with jet-black hair and shopping lodged safely between their feet. Good times, but the flat became too small and we moved on, eventually leaving Rome. We had no idea that twenty-two years later we would be back in San Lorenzo, on a temporary basis that turned out be less temporary than we’d imagined. We spent the first lockdown there, and watched the students leave and the seagulls take over Piazza dell’Immacolata and the bars put up their shutters.

Eleven years after that first plate of spaghetti alle vongole I found myself living three streets away and then, a few months later, almost directly opposite da Franco. The flat was tiny, but we were grateful to be back in Rome and to have what passed for a terrace, overlooked on all sides by taller buildings with external balconies and occasionally used as a bin for cigarette ends, scraps of paper, sweet wrappers and used condoms, which we would sweep up every few days. We stayed there for a few years, making friends with our neighbours in the other three flats in the building and becoming regulars at Bar Marani, a bar whose clientele covered the entire demographic of the quarter, from creative types, impecunious and otherwise, to signore of a certain age with jet-black hair and shopping lodged safely between their feet. Good times, but the flat became too small and we moved on, eventually leaving Rome. We had no idea that twenty-two years later we would be back in San Lorenzo, on a temporary basis that turned out be less temporary than we’d imagined. We spent the first lockdown there, and watched the students leave and the seagulls take over Piazza dell’Immacolata and the bars put up their shutters.

6. NOTE

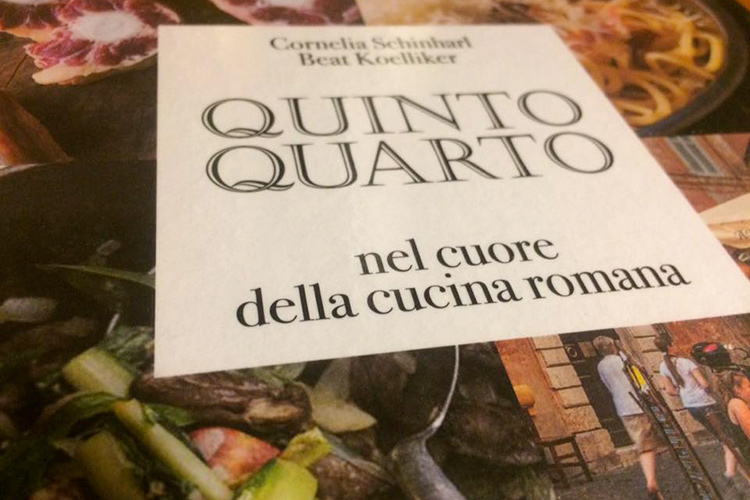

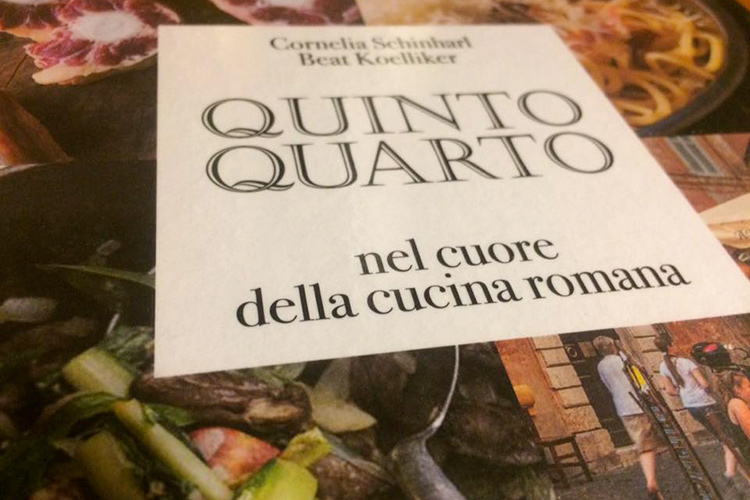

The title of this piece is a play on words. Five quarters of the city, using the word quarter in its Italian or French sense is the primary meaning. But to a Roman the term ‘quinto quarto’ or ‘fifth quarter’ refers to offal, to what’s left when the animal has been butchered and divided into four to be sold. The fifth quarter is the part of the animal reserved for those who would otherwise have nothing, and has provided Roman cooking with some of its most delicious, and typical, dishes. Coda, coratella, pajata. Rome is a city that makes do with what it has, that complains about everything and then finds a way to make what’s wrong work in its favour—si arrangia, as the Italian has it. It isn’t an easy city, but then, life isn’t. Like Augusto’s, its heart is often concealed. Maybe Augusto’s son had the words for it.

The title of this piece is a play on words. Five quarters of the city, using the word quarter in its Italian or French sense is the primary meaning. But to a Roman the term ‘quinto quarto’ or ‘fifth quarter’ refers to offal, to what’s left when the animal has been butchered and divided into four to be sold. The fifth quarter is the part of the animal reserved for those who would otherwise have nothing, and has provided Roman cooking with some of its most delicious, and typical, dishes. Coda, coratella, pajata. Rome is a city that makes do with what it has, that complains about everything and then finds a way to make what’s wrong work in its favour—si arrangia, as the Italian has it. It isn’t an easy city, but then, life isn’t. Like Augusto’s, its heart is often concealed. Maybe Augusto’s son had the words for it.

Uno stronzo per bene.

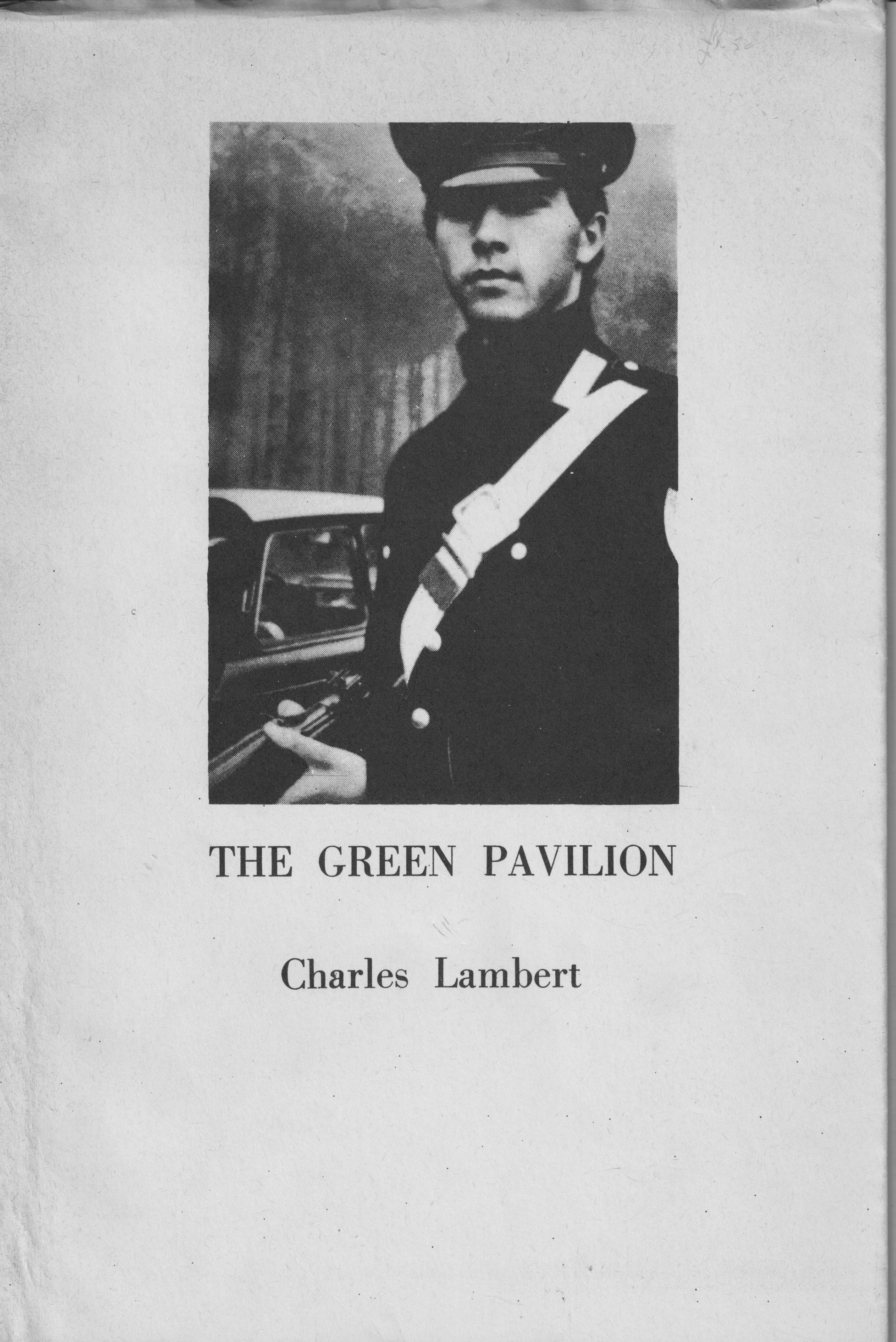

The cover I used came from a weekly magazine, Espresso or Panorama, and was part of a photograph used to illustrate an article about a clampdown on the ‘Ndrangheta in Calabria. All it had to do with the work of Genet was what I must have seen at the time as a rough, potentially dangerous, uniformed masculinity, although looking at it now the most obvious quality is a rather cute vulnerability. I may have confused the two, or hoped that the former would necessarily conceal the latter and that I would be the one to find this out. I wondered later what the young man would have thought of his image being identified with a collection of subversive, erotic verse. Still, what isn’t known can’t hurt and the chances of a copy of the pamphlet finding its way into a Calabrian barracks were small then, and are even smaller now, the only remaining copies being stored away in a box beneath a spare bed. But it’s odd to think how taken I was by this image, by this young man with his rifle and putto-esque good looks, and how I saw him as representing the thuggish heroes that strode through Genet’s dreams of possession and being possessed.

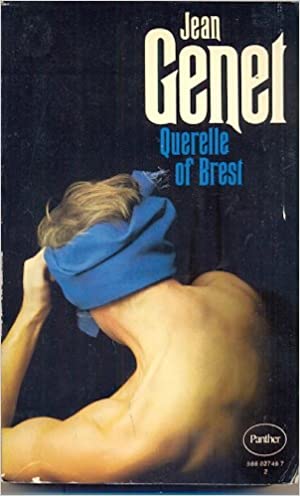

The cover I used came from a weekly magazine, Espresso or Panorama, and was part of a photograph used to illustrate an article about a clampdown on the ‘Ndrangheta in Calabria. All it had to do with the work of Genet was what I must have seen at the time as a rough, potentially dangerous, uniformed masculinity, although looking at it now the most obvious quality is a rather cute vulnerability. I may have confused the two, or hoped that the former would necessarily conceal the latter and that I would be the one to find this out. I wondered later what the young man would have thought of his image being identified with a collection of subversive, erotic verse. Still, what isn’t known can’t hurt and the chances of a copy of the pamphlet finding its way into a Calabrian barracks were small then, and are even smaller now, the only remaining copies being stored away in a box beneath a spare bed. But it’s odd to think how taken I was by this image, by this young man with his rifle and putto-esque good looks, and how I saw him as representing the thuggish heroes that strode through Genet’s dreams of possession and being possessed. Genet was one of the two or three writers who helped me come to terms with my sexuality when I was a teenager. The others were probably Christopher Isherwood and Michel Tournier. Genet understood better than anyone what it was like to be an outcast, to be despised, to transform that contempt into an erotic covering and weapon, a protection that allowed the self to survive and even thrive on punishment. He also appreciated the redemptive value of revenge, even of the purely imagined kind. I was fourteen when homosexuality ceased to be a punishable offence in the United Kingdom and its removal from the criminal code made little difference to the actual business of living the life of a gay teenager attending a comprehensive in a small provincial town, where invisibility and the eroticisation of internalised shame were the only refuges available, apart from the greatest and most saving grace of all, that provided by books. To get hold of the books I wanted to read I had to order them from the town’s bookseller-cum-newsagent, Fred Hill, on Derby St. This meant enduring the puzzled and slightly disdainful look of whoever happened to be taking the order, and praying that the cover of the book would not be too obvious. Obviousness was the arch sin, whether in one’s manner, one’s speech or one’s book choices. After all, anyone might be in the shop when the book arrived, and no brown paper bag was fast enough to foil the attentive eye of an inquisitive, and potentially inquisitorial, customer. The covers of my first two purchases, The Miracle of the Rose (Dalì) and The Thief’s Journal (Tanguy), both Penguin Modern Classics, were odd, disturbingly so, but branded me as, at worst, an intellectual. The Grove Press edition of Our Lady of the Flowers – the face of a young man, apparently dead, surrounded by leaves – was a little more risky but just passed muster.

Genet was one of the two or three writers who helped me come to terms with my sexuality when I was a teenager. The others were probably Christopher Isherwood and Michel Tournier. Genet understood better than anyone what it was like to be an outcast, to be despised, to transform that contempt into an erotic covering and weapon, a protection that allowed the self to survive and even thrive on punishment. He also appreciated the redemptive value of revenge, even of the purely imagined kind. I was fourteen when homosexuality ceased to be a punishable offence in the United Kingdom and its removal from the criminal code made little difference to the actual business of living the life of a gay teenager attending a comprehensive in a small provincial town, where invisibility and the eroticisation of internalised shame were the only refuges available, apart from the greatest and most saving grace of all, that provided by books. To get hold of the books I wanted to read I had to order them from the town’s bookseller-cum-newsagent, Fred Hill, on Derby St. This meant enduring the puzzled and slightly disdainful look of whoever happened to be taking the order, and praying that the cover of the book would not be too obvious. Obviousness was the arch sin, whether in one’s manner, one’s speech or one’s book choices. After all, anyone might be in the shop when the book arrived, and no brown paper bag was fast enough to foil the attentive eye of an inquisitive, and potentially inquisitorial, customer. The covers of my first two purchases, The Miracle of the Rose (Dalì) and The Thief’s Journal (Tanguy), both Penguin Modern Classics, were odd, disturbingly so, but branded me as, at worst, an intellectual. The Grove Press edition of Our Lady of the Flowers – the face of a young man, apparently dead, surrounded by leaves – was a little more risky but just passed muster. , published by Panther in 1969, when I was fifteen, was another kettle of fish entirely and I don’t know how I managed to smuggle it out of the shop and into my bedroom without mishap. It’s hard to imagine now, with the naked or semi-naked male body as objectified and primped and packaged as the female body, just how rare it was to catch a glimpse of exposed male skin. I cunningly recycled a Stoke-on-Trent Arts Festival programme as a makeshift scrapbook for my cache of men with at least some of their togs off, footballers usually, the occasional actor from a film starring gladiators or mythical heroes, a memorable photo of Starsky in bondage and not much else. The only source of full-frontal male nudity was the naturist magazine Health and Efficiency. But I digress. Given the nature of the text, perhaps the most available and explicit of all Genet’s novels, it was perhaps fitting that the cover of Querelle should be the most unequivocal of those given to the English translations, and it’s no surprise that it should be the only novel to be filmed, in an exemplary manner, by Fassbinder. Talking of which, Brad Davis was as close to my notion of an ideal Genet hero as might be imagined, and I bought the set of Warhol prints made to accompany the film and had them framed and hung on the wall of the flat I shared with friends in Rome, a sign if nothing else of how much the times and my life within them had changed.

, published by Panther in 1969, when I was fifteen, was another kettle of fish entirely and I don’t know how I managed to smuggle it out of the shop and into my bedroom without mishap. It’s hard to imagine now, with the naked or semi-naked male body as objectified and primped and packaged as the female body, just how rare it was to catch a glimpse of exposed male skin. I cunningly recycled a Stoke-on-Trent Arts Festival programme as a makeshift scrapbook for my cache of men with at least some of their togs off, footballers usually, the occasional actor from a film starring gladiators or mythical heroes, a memorable photo of Starsky in bondage and not much else. The only source of full-frontal male nudity was the naturist magazine Health and Efficiency. But I digress. Given the nature of the text, perhaps the most available and explicit of all Genet’s novels, it was perhaps fitting that the cover of Querelle should be the most unequivocal of those given to the English translations, and it’s no surprise that it should be the only novel to be filmed, in an exemplary manner, by Fassbinder. Talking of which, Brad Davis was as close to my notion of an ideal Genet hero as might be imagined, and I bought the set of Warhol prints made to accompany the film and had them framed and hung on the wall of the flat I shared with friends in Rome, a sign if nothing else of how much the times and my life within them had changed.

(Discipline Arti Musica Spettacolo), actors, directors, musicians, screenplay writers and, alas, bar staff. The physical teaching conditions were, by Italian university standards, surprisingly adequate: well-lit classrooms with the required audio-visual equipment, teacher visible to all (a sine qua non in most academes but not necessarily in Rome) and chair-desk combinations designed for human beings, at the outset at least. But what made the teaching so stimulating was the range of experiences, and aspirations, the students brought to the lessons. Not all of them were initially happy to be there, regarding the pursuit of the last colonial vestige of the Empire as irrelevant to their main interests, and it was part of my job – a part I relished – to persuade them that this wasn’t the case. Others, the majority, were Anglophiles in one way or another, in love with the music or the art galleries or the pubs, with London, or an idea of London, eager to take advantage of Erasmus (don’t go there, Charles, just don’t) and seeing the class as an opportunity to deepen and extend that love. I have nothing but fond memories of my time in the classroom there and one of the groups I particularly enjoyed teaching turned up in my last year, initially in the classroom and then, as COVID hit, at least in part online. Two members of that group, Joshua De Loa and Alessia Marini, contacted me last autumn to ask me if I’d be prepared to be interviewed by them for

(Discipline Arti Musica Spettacolo), actors, directors, musicians, screenplay writers and, alas, bar staff. The physical teaching conditions were, by Italian university standards, surprisingly adequate: well-lit classrooms with the required audio-visual equipment, teacher visible to all (a sine qua non in most academes but not necessarily in Rome) and chair-desk combinations designed for human beings, at the outset at least. But what made the teaching so stimulating was the range of experiences, and aspirations, the students brought to the lessons. Not all of them were initially happy to be there, regarding the pursuit of the last colonial vestige of the Empire as irrelevant to their main interests, and it was part of my job – a part I relished – to persuade them that this wasn’t the case. Others, the majority, were Anglophiles in one way or another, in love with the music or the art galleries or the pubs, with London, or an idea of London, eager to take advantage of Erasmus (don’t go there, Charles, just don’t) and seeing the class as an opportunity to deepen and extend that love. I have nothing but fond memories of my time in the classroom there and one of the groups I particularly enjoyed teaching turned up in my last year, initially in the classroom and then, as COVID hit, at least in part online. Two members of that group, Joshua De Loa and Alessia Marini, contacted me last autumn to ask me if I’d be prepared to be interviewed by them for  These days, to imagine a world in which you don’t exist is to imagine a world in which you have never been photographed. We’re so used to seeing ourselves, stabilised by selfies, profile photos, snapchat, looped snippets of movement on Vine. A smile. A shake of the head. Full-on, three-quarter, profile. We ply each other with pictures of how we look as though we no longer needed, or possessed, the use of memory. How accustomed we’ve grown to the ease of this, this ever lengthening catalogue of who we are, this ballast of images that shores us up and defines us, knowing and self-aware as we stare into the greedy uncritical surface of our smartphones and tablets. We click on beauty face or contrast, we fiddle with lighting and focus, to make sure what we’re seeing, and sending, is really us, the us we recognise. The us we know we know.

These days, to imagine a world in which you don’t exist is to imagine a world in which you have never been photographed. We’re so used to seeing ourselves, stabilised by selfies, profile photos, snapchat, looped snippets of movement on Vine. A smile. A shake of the head. Full-on, three-quarter, profile. We ply each other with pictures of how we look as though we no longer needed, or possessed, the use of memory. How accustomed we’ve grown to the ease of this, this ever lengthening catalogue of who we are, this ballast of images that shores us up and defines us, knowing and self-aware as we stare into the greedy uncritical surface of our smartphones and tablets. We click on beauty face or contrast, we fiddle with lighting and focus, to make sure what we’re seeing, and sending, is really us, the us we recognise. The us we know we know. But it wasn’t always like this. I took my first photos, or ‘snaps’, as we used to say, with a Kodak Brownie Flash IV, a box-shaped camera made out of leatherette-covered cardboard, with a fixed lens at the front, a viewfinder at the top and a shutter release lever on the right-hand side. I’d hold the box at waist level and depress the lever to take a photograph, careful not to jog it as I did so. It didn’t occur to me then – why should it have done? – that the one thing I could never do was take a photo of myself. (By ‘myself’, of course, I mean my face.) In order to take the photo I needed to look down. Looking up, I had no idea what the lens might be framing. Photography was reflexive, but not self-reflexive. Selfies, in other words, were not an option. You could always persuade someone else to take your photograph, of course. The younger, and cuter, you were, the likelier it was that you’d succeed. Being first-born also helped. What family album (remember those?) didn’t have a dozen times as many pages devoted to the eldest child as to those who came later, to their justifiable chagrin?

But it wasn’t always like this. I took my first photos, or ‘snaps’, as we used to say, with a Kodak Brownie Flash IV, a box-shaped camera made out of leatherette-covered cardboard, with a fixed lens at the front, a viewfinder at the top and a shutter release lever on the right-hand side. I’d hold the box at waist level and depress the lever to take a photograph, careful not to jog it as I did so. It didn’t occur to me then – why should it have done? – that the one thing I could never do was take a photo of myself. (By ‘myself’, of course, I mean my face.) In order to take the photo I needed to look down. Looking up, I had no idea what the lens might be framing. Photography was reflexive, but not self-reflexive. Selfies, in other words, were not an option. You could always persuade someone else to take your photograph, of course. The younger, and cuter, you were, the likelier it was that you’d succeed. Being first-born also helped. What family album (remember those?) didn’t have a dozen times as many pages devoted to the eldest child as to those who came later, to their justifiable chagrin? Until very recently, photography was expensive. There was the cost of the actual film, which had to be taken from its cardboard box, removed from its special protective packaging, inserted into the camera and lined up with the internal sprocket, ready to be wound on, at which point the camera case was closed and the film could no longer be exposed to the light, and any mistakes that might have been made were irremediable. All film, black and white even more than colour, was pricey and the price shot up if you wanted an ASA that wasn’t the standard 100. (I’m losing you, aren’t I? ASA became ISO, if that’s any help.) There were economies of scale, of course. A 36 shot film cost less than half as much again as one with only 24 shots, but the downside was that you had to be patient that much longer. What all this meant though was that, before you took a photograph, you thought about it. A photograph was a contract you made with the world, a relationship governed by economics, sentiment and aesthetic sense. It had a certain weight.

Until very recently, photography was expensive. There was the cost of the actual film, which had to be taken from its cardboard box, removed from its special protective packaging, inserted into the camera and lined up with the internal sprocket, ready to be wound on, at which point the camera case was closed and the film could no longer be exposed to the light, and any mistakes that might have been made were irremediable. All film, black and white even more than colour, was pricey and the price shot up if you wanted an ASA that wasn’t the standard 100. (I’m losing you, aren’t I? ASA became ISO, if that’s any help.) There were economies of scale, of course. A 36 shot film cost less than half as much again as one with only 24 shots, but the downside was that you had to be patient that much longer. What all this meant though was that, before you took a photograph, you thought about it. A photograph was a contract you made with the world, a relationship governed by economics, sentiment and aesthetic sense. It had a certain weight. And then, once the film had been finished, rewound and removed from the camera, carefully to avoid unwanted exposure, it had to be developed. Real buffs had their own dark room; for the rest of us, the most likely option was the local chemist. It wasn’t cheap and the pleasure of seeing what you’d done was delayed by days or, for an extra charge, by 24 hours. The photographs came back in a sort of folder, usually Kodak yellow, with the negatives in their own little pocket and were, in my experience, almost invariably a disappointment, a gratification both deferred and subtly unfulfilled. Like good cheese or sloe gin, photographs needed time to mature. They needed you to move on, until what they showed you was muted or glazed by nostalgia.

And then, once the film had been finished, rewound and removed from the camera, carefully to avoid unwanted exposure, it had to be developed. Real buffs had their own dark room; for the rest of us, the most likely option was the local chemist. It wasn’t cheap and the pleasure of seeing what you’d done was delayed by days or, for an extra charge, by 24 hours. The photographs came back in a sort of folder, usually Kodak yellow, with the negatives in their own little pocket and were, in my experience, almost invariably a disappointment, a gratification both deferred and subtly unfulfilled. Like good cheese or sloe gin, photographs needed time to mature. They needed you to move on, until what they showed you was muted or glazed by nostalgia. How much of the web of memories, half-memories and appropriated memories that make up our past is dependent on the photographic record? A record as broken, spasmodic, interrupted as the fossil record of the human species. Holidays when no one had a camera have a different, after-the-event existence from the ones that were documented, if they exist at all. There are beaches in my childhood of which I have no memory, others in which I could touch each rock pool, run from each wave and yet some of them are black and white because my father liked to experiment, or coloured in the candy-like colours of 1960s slides, or the shades are too vivid because he read his light meter wrong. There is a series of slides he took of me one holiday in Wales. The weather was stormy and we were waiting by the breakwater of a pebbled beach for my mother to come out of the hairdressers. I am throwing stones into the sea, not skimming them as my father did, but hurling them as hard as I can, in what looks like a rage I no longer know the reason for, and an exhilaration that’s almost entirely the result of my father’s dramatic handling of the light and of the curve my arm makes as I throw. The rest of the holiday might never have been.

How much of the web of memories, half-memories and appropriated memories that make up our past is dependent on the photographic record? A record as broken, spasmodic, interrupted as the fossil record of the human species. Holidays when no one had a camera have a different, after-the-event existence from the ones that were documented, if they exist at all. There are beaches in my childhood of which I have no memory, others in which I could touch each rock pool, run from each wave and yet some of them are black and white because my father liked to experiment, or coloured in the candy-like colours of 1960s slides, or the shades are too vivid because he read his light meter wrong. There is a series of slides he took of me one holiday in Wales. The weather was stormy and we were waiting by the breakwater of a pebbled beach for my mother to come out of the hairdressers. I am throwing stones into the sea, not skimming them as my father did, but hurling them as hard as I can, in what looks like a rage I no longer know the reason for, and an exhilaration that’s almost entirely the result of my father’s dramatic handling of the light and of the curve my arm makes as I throw. The rest of the holiday might never have been. Which is why it can be so disconcerting to come across a photograph of yourself from a period you thought was already accounted for in the record. I spent the first part of the 1980s in northern Italy. I had a camera, an SLR, my friends had cameras. We never moved without them. I thought I had copies of every photo taken of me during those years, and the following years in Rome, until I was at a party over thirty years later, of one of the group and there I was on a pin board, my friend and I, smiling at whoever held the camera, and I saw an expression on my face that I didn’t recognise as mine. I was moved to the point of tears. Who is this man, I thought, and how can I have lost him so completely, only to find him here again, as if we have never been parted? What must it have been like to be him? to be me? And how many other images of me, I wondered, must be pinned to other walls, or stuffed into drawers? It isn’t a question of the photograph stealing the soul, that primitive fear, but of something more fleeting, some fragment of fossilised bone that both confirms and challenges our knowledge of what we are. A small gap in the record closed.

Which is why it can be so disconcerting to come across a photograph of yourself from a period you thought was already accounted for in the record. I spent the first part of the 1980s in northern Italy. I had a camera, an SLR, my friends had cameras. We never moved without them. I thought I had copies of every photo taken of me during those years, and the following years in Rome, until I was at a party over thirty years later, of one of the group and there I was on a pin board, my friend and I, smiling at whoever held the camera, and I saw an expression on my face that I didn’t recognise as mine. I was moved to the point of tears. Who is this man, I thought, and how can I have lost him so completely, only to find him here again, as if we have never been parted? What must it have been like to be him? to be me? And how many other images of me, I wondered, must be pinned to other walls, or stuffed into drawers? It isn’t a question of the photograph stealing the soul, that primitive fear, but of something more fleeting, some fragment of fossilised bone that both confirms and challenges our knowledge of what we are. A small gap in the record closed. When we finally reached the ring road surrounding Rome, Sue decided we should find a hotel outside the centre, where Lucifero would be welcome. We drove to Ostia, the setting for scenes from some of Pasolini’s grittily realistic films and, the year before our visit, his grittily realistic death. The only hotel with vacancies was a stuccoed beige block with a chilly veranda-cum-dining room attached to the front. The rooms were bare, uninviting, damp. This looks fine, said Sue, who’d promised to pay. After we’d heaved her enormous suitcase onto her bed, Charlie and I mooned along the beach, taking photographs of chipped blue-painted changing cubicles and boarded-up bars while Sue unpacked, Lucifero barking frantically at the cold grey sea.

When we finally reached the ring road surrounding Rome, Sue decided we should find a hotel outside the centre, where Lucifero would be welcome. We drove to Ostia, the setting for scenes from some of Pasolini’s grittily realistic films and, the year before our visit, his grittily realistic death. The only hotel with vacancies was a stuccoed beige block with a chilly veranda-cum-dining room attached to the front. The rooms were bare, uninviting, damp. This looks fine, said Sue, who’d promised to pay. After we’d heaved her enormous suitcase onto her bed, Charlie and I mooned along the beach, taking photographs of chipped blue-painted changing cubicles and boarded-up bars while Sue unpacked, Lucifero barking frantically at the cold grey sea. We ate that evening in a restaurant on the road to Ostia, two hundred yards from the catacombs and the Appian Way. The outer walls were encrusted with shards of pottery and scraps of Roman statuary. Inside, the place was empty. We stood by the door, Lucifero skulking at Sue’s heel. After a moment, muttering from behind a screen painted in Pompeii red was followed by what sounded like a thump. A waiter appeared in the breastplate and pleated miniskirt of a gladiator. When Sue began to giggle, the waiter froze, then turned to hiss at whoever was standing behind him. Eventually we were served. The food was dreadful, though we didn’t realise how dreadful at the time. We barely noticed what we ate as the restaurant filled with coach-loads of hungry pilgrims and what looked like the cast of Ben Hur passed by bearing plates of lukewarm pasta alla carbonara.

We ate that evening in a restaurant on the road to Ostia, two hundred yards from the catacombs and the Appian Way. The outer walls were encrusted with shards of pottery and scraps of Roman statuary. Inside, the place was empty. We stood by the door, Lucifero skulking at Sue’s heel. After a moment, muttering from behind a screen painted in Pompeii red was followed by what sounded like a thump. A waiter appeared in the breastplate and pleated miniskirt of a gladiator. When Sue began to giggle, the waiter froze, then turned to hiss at whoever was standing behind him. Eventually we were served. The food was dreadful, though we didn’t realise how dreadful at the time. We barely noticed what we ate as the restaurant filled with coach-loads of hungry pilgrims and what looked like the cast of Ben Hur passed by bearing plates of lukewarm pasta alla carbonara. I passed my days waiting for the phonogram from the Ministry of Education that would confirm my contract, wandering around the station and the surrounding area, then down Via Nazionale to the rest of the city. I spoke to almost no one other than waiters in restaurants and the harassed English professor responsible for my contract. Friends who knew Rome had recommended restaurants that were good or cheap, but never both. It didn’t take long to move from the first group to the second. Mario’s (aka the Poisoner) in Trastevere – where you could eat a plate of pasta with oil, garlic and chilli pepper for less than 40p – was a favourite. Just round the corner, in Piazza de’ Renzi, was da Augusto, a trattoria with paper tablecloths and Castelli Romani wine on tap, run by a grumpy old man – presumably Augusto – with a speech defect and an upwardly mobile son. The fourth time I went there, I’d spoken to no one for almost three days. When Grumpy flung the menu onto the table and snapped at me that the lamb was off, I burst into unexpected tears. He hugged me, once, and brought me wine and bread. I’ve never been more grateful to anyone in my life, though his tone didn’t change and I was never hugged again. At a party years later I bumped into his son, accompanied by a glamorous American model, and told him what his father had done. ‘È sempre stato uno stronzo per bene,’ his son said cheerfully. He’s always been a decent sort of shit.

I passed my days waiting for the phonogram from the Ministry of Education that would confirm my contract, wandering around the station and the surrounding area, then down Via Nazionale to the rest of the city. I spoke to almost no one other than waiters in restaurants and the harassed English professor responsible for my contract. Friends who knew Rome had recommended restaurants that were good or cheap, but never both. It didn’t take long to move from the first group to the second. Mario’s (aka the Poisoner) in Trastevere – where you could eat a plate of pasta with oil, garlic and chilli pepper for less than 40p – was a favourite. Just round the corner, in Piazza de’ Renzi, was da Augusto, a trattoria with paper tablecloths and Castelli Romani wine on tap, run by a grumpy old man – presumably Augusto – with a speech defect and an upwardly mobile son. The fourth time I went there, I’d spoken to no one for almost three days. When Grumpy flung the menu onto the table and snapped at me that the lamb was off, I burst into unexpected tears. He hugged me, once, and brought me wine and bread. I’ve never been more grateful to anyone in my life, though his tone didn’t change and I was never hugged again. At a party years later I bumped into his son, accompanied by a glamorous American model, and told him what his father had done. ‘È sempre stato uno stronzo per bene,’ his son said cheerfully. He’s always been a decent sort of shit. By day, though, it was churches and ruins. Obsessed by the Pantheon, my favourite building, I passed hours beneath its perfect dome, hoping for rain so that I could watch it enter through the central hole and sparkle white-gold as it fell. One May, a year or two later, I happened to be there for Pentecost, when firemen empty sacks of rose petals through the hole in the dome, a practice that began when Rome was home of emperors, until the interior is rippled by red-reflected light, the ancient floor a scented carpet lifted by breeze. I stared at the Byzantine mosaics in Santa Prassede for hours. I did the Borromini trail, from Sant’Agnese to Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, learning about Baroque by stroking its warm curves with my hands.

By day, though, it was churches and ruins. Obsessed by the Pantheon, my favourite building, I passed hours beneath its perfect dome, hoping for rain so that I could watch it enter through the central hole and sparkle white-gold as it fell. One May, a year or two later, I happened to be there for Pentecost, when firemen empty sacks of rose petals through the hole in the dome, a practice that began when Rome was home of emperors, until the interior is rippled by red-reflected light, the ancient floor a scented carpet lifted by breeze. I stared at the Byzantine mosaics in Santa Prassede for hours. I did the Borromini trail, from Sant’Agnese to Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, learning about Baroque by stroking its warm curves with my hands. My first real Roman home was in Testaccio: home in the sense that I didn’t pay by the day. I’d started work at the university and one of the professors said that her daughter had a room I could use if I didn’t mind roughing it. I went round that afternoon. The flat was on the second floor of a 19th century block, with a trattoria opposite that sold Marino wine by the litre. The Protestant cemetery was down the road and Monte Testaccio, the heap of ancient rubble that gave the district its name, a few minutes’ walk away. Miranda showed me the room and I understood what her mother had meant. There was a metal-framed bed in one corner and a trestle table in another, a single straight-backed chair. I didn’t care; I had a wall against which to stack my books and a floor to dump my suitcase on. Best of all, I could use the kitchen.

My first real Roman home was in Testaccio: home in the sense that I didn’t pay by the day. I’d started work at the university and one of the professors said that her daughter had a room I could use if I didn’t mind roughing it. I went round that afternoon. The flat was on the second floor of a 19th century block, with a trattoria opposite that sold Marino wine by the litre. The Protestant cemetery was down the road and Monte Testaccio, the heap of ancient rubble that gave the district its name, a few minutes’ walk away. Miranda showed me the room and I understood what her mother had meant. There was a metal-framed bed in one corner and a trestle table in another, a single straight-backed chair. I didn’t care; I had a wall against which to stack my books and a floor to dump my suitcase on. Best of all, I could use the kitchen. I moved back to Testaccio four years later, with my partner, to a three-roomed flat overlooking the more elegant of its two squares: Piazza Santa Maria Liberatrice, the one with the local church and the working theatre, rather than the smaller one round the corner where the food market was, although it’s since been moved. We had a flat on the top floor, our windows more or less level with the tops of the maritime pines rising from the gardens below. Our building was next to the one in which Gabriella Ferri, the Roman folk singer, had been born; there was great excitement when RAI television came to film her in the entrance, not long before she killed herself. A friend of mine bumped into her once in the Alibi, the gay club carved into the side of Monte Testaccio. She asked him if he had a joint, then drifted off, majestic and blonde and lost, before he had a chance to answer. More recently, Nicole Kidman pretended to be a Roman housewife on its roof terrace, pinning out her washing for an advertisement.

I moved back to Testaccio four years later, with my partner, to a three-roomed flat overlooking the more elegant of its two squares: Piazza Santa Maria Liberatrice, the one with the local church and the working theatre, rather than the smaller one round the corner where the food market was, although it’s since been moved. We had a flat on the top floor, our windows more or less level with the tops of the maritime pines rising from the gardens below. Our building was next to the one in which Gabriella Ferri, the Roman folk singer, had been born; there was great excitement when RAI television came to film her in the entrance, not long before she killed herself. A friend of mine bumped into her once in the Alibi, the gay club carved into the side of Monte Testaccio. She asked him if he had a joint, then drifted off, majestic and blonde and lost, before he had a chance to answer. More recently, Nicole Kidman pretended to be a Roman housewife on its roof terrace, pinning out her washing for an advertisement. I finally made it to the historic centre in my fourth year in Rome, moving into a shabbily splendid flat in Piazza Santa Caterina della Rota, the martyred virgin and founder, albeit unwillingly, of the Catherine wheel, just round the corner from Piazza Farnese, opposite the English College. I shared four hundred square metres – the entire second floor, the one above the piano nobile traditionally reserved for the building’s owners – with an English colleague and an American woman. The British Embassy had rented the place for its lowlier diplomatic staff, but it had fallen into my colleague’s hands and we lived there with remnants of its past, two broken-down but comfortable sofas, a dining table that would happily seat twenty, Murano chandeliers dangling imposingly from most of the ceilings, a kitchen only servants could be expected to work in, two poky bathrooms fitted in anyhow, as an afterthought or concession to mere bodily needs. The doors and ceilings were decorated with painted curls and floral business, lovelier for being faded. It was all I could do to sleep, my bed beneath a meringue of glass and pastel wreaths. Beneath my bedroom window was one of the few remaining petrol pumps in the city centre, and a bicycle shop. Their metal shutters, pushed noisily home, woke me each weekday morning at eight o’clock. With my windows thrown open, I could hear the seminarians in the street below as they bitched about one another or the older priests in their shrill camp voices, imagining themselves unheard. In the echoing high-ceilinged rooms, the three of us lived our separate lives as though we’d been billeted there in wartime and the owners had carried off what they could before the barbarians arrived.

I finally made it to the historic centre in my fourth year in Rome, moving into a shabbily splendid flat in Piazza Santa Caterina della Rota, the martyred virgin and founder, albeit unwillingly, of the Catherine wheel, just round the corner from Piazza Farnese, opposite the English College. I shared four hundred square metres – the entire second floor, the one above the piano nobile traditionally reserved for the building’s owners – with an English colleague and an American woman. The British Embassy had rented the place for its lowlier diplomatic staff, but it had fallen into my colleague’s hands and we lived there with remnants of its past, two broken-down but comfortable sofas, a dining table that would happily seat twenty, Murano chandeliers dangling imposingly from most of the ceilings, a kitchen only servants could be expected to work in, two poky bathrooms fitted in anyhow, as an afterthought or concession to mere bodily needs. The doors and ceilings were decorated with painted curls and floral business, lovelier for being faded. It was all I could do to sleep, my bed beneath a meringue of glass and pastel wreaths. Beneath my bedroom window was one of the few remaining petrol pumps in the city centre, and a bicycle shop. Their metal shutters, pushed noisily home, woke me each weekday morning at eight o’clock. With my windows thrown open, I could hear the seminarians in the street below as they bitched about one another or the older priests in their shrill camp voices, imagining themselves unheard. In the echoing high-ceilinged rooms, the three of us lived our separate lives as though we’d been billeted there in wartime and the owners had carried off what they could before the barbarians arrived. I first lived in San Lorenzo when we moved back to Rome in 1991 after a failed attempt to relocate in London, but the district had always been on my personal map of the city since I was first taken to da Franco, a fish restaurant in Via dei Falisci, famous for being cheap, generous with its portions and not a risk to health. Residential San Lorenzo is wedged into a sort of quadrilateral, with Termini and the city’s historic cemetery, Verano, roughly to its west and east, while to the south lies Scalo di San Lorenzo, a square kilometre or so of railway lines representing the main transport hub of the capital and the reason the district was bombed more heavily than any other during World War Two; the scars can still be seen. Like Testaccio, it was predominantly working class; unlike Testaccio, it still is, although the proximity of Rome’s main university, La Sapienza, to the north of the area, has led to an influx of students, sharing rooms in hastily converted, over-priced apartments and enlivening the early hours in a variety of bars and pizzerias, much to the chagrin of those historic residents who haven’t let their homes and loved somewhere quieter.

I first lived in San Lorenzo when we moved back to Rome in 1991 after a failed attempt to relocate in London, but the district had always been on my personal map of the city since I was first taken to da Franco, a fish restaurant in Via dei Falisci, famous for being cheap, generous with its portions and not a risk to health. Residential San Lorenzo is wedged into a sort of quadrilateral, with Termini and the city’s historic cemetery, Verano, roughly to its west and east, while to the south lies Scalo di San Lorenzo, a square kilometre or so of railway lines representing the main transport hub of the capital and the reason the district was bombed more heavily than any other during World War Two; the scars can still be seen. Like Testaccio, it was predominantly working class; unlike Testaccio, it still is, although the proximity of Rome’s main university, La Sapienza, to the north of the area, has led to an influx of students, sharing rooms in hastily converted, over-priced apartments and enlivening the early hours in a variety of bars and pizzerias, much to the chagrin of those historic residents who haven’t let their homes and loved somewhere quieter. Eleven years after that first plate of spaghetti alle vongole I found myself living three streets away and then, a few months later, almost directly opposite da Franco. The flat was tiny, but we were grateful to be back in Rome and to have what passed for a terrace, overlooked on all sides by taller buildings with external balconies and occasionally used as a bin for cigarette ends, scraps of paper, sweet wrappers and used condoms, which we would sweep up every few days. We stayed there for a few years, making friends with our neighbours in the other three flats in the building and becoming regulars at Bar Marani, a bar whose clientele covered the entire demographic of the quarter, from creative types, impecunious and otherwise, to signore of a certain age with jet-black hair and shopping lodged safely between their feet. Good times, but the flat became too small and we moved on, eventually leaving Rome. We had no idea that twenty-two years later we would be back in San Lorenzo, on a temporary basis that turned out be less temporary than we’d imagined. We spent the first lockdown there, and watched the students leave and the seagulls take over Piazza dell’Immacolata and the bars put up their shutters.

Eleven years after that first plate of spaghetti alle vongole I found myself living three streets away and then, a few months later, almost directly opposite da Franco. The flat was tiny, but we were grateful to be back in Rome and to have what passed for a terrace, overlooked on all sides by taller buildings with external balconies and occasionally used as a bin for cigarette ends, scraps of paper, sweet wrappers and used condoms, which we would sweep up every few days. We stayed there for a few years, making friends with our neighbours in the other three flats in the building and becoming regulars at Bar Marani, a bar whose clientele covered the entire demographic of the quarter, from creative types, impecunious and otherwise, to signore of a certain age with jet-black hair and shopping lodged safely between their feet. Good times, but the flat became too small and we moved on, eventually leaving Rome. We had no idea that twenty-two years later we would be back in San Lorenzo, on a temporary basis that turned out be less temporary than we’d imagined. We spent the first lockdown there, and watched the students leave and the seagulls take over Piazza dell’Immacolata and the bars put up their shutters. The title of this piece is a play on words. Five quarters of the city, using the word quarter in its Italian or French sense is the primary meaning. But to a Roman the term ‘quinto quarto’ or ‘fifth quarter’ refers to offal, to what’s left when the animal has been butchered and divided into four to be sold. The fifth quarter is the part of the animal reserved for those who would otherwise have nothing, and has provided Roman cooking with some of its most delicious, and typical, dishes. Coda, coratella, pajata. Rome is a city that makes do with what it has, that complains about everything and then finds a way to make what’s wrong work in its favour—si arrangia, as the Italian has it. It isn’t an easy city, but then, life isn’t. Like Augusto’s, its heart is often concealed. Maybe Augusto’s son had the words for it.

The title of this piece is a play on words. Five quarters of the city, using the word quarter in its Italian or French sense is the primary meaning. But to a Roman the term ‘quinto quarto’ or ‘fifth quarter’ refers to offal, to what’s left when the animal has been butchered and divided into four to be sold. The fifth quarter is the part of the animal reserved for those who would otherwise have nothing, and has provided Roman cooking with some of its most delicious, and typical, dishes. Coda, coratella, pajata. Rome is a city that makes do with what it has, that complains about everything and then finds a way to make what’s wrong work in its favour—si arrangia, as the Italian has it. It isn’t an easy city, but then, life isn’t. Like Augusto’s, its heart is often concealed. Maybe Augusto’s son had the words for it. “Death hovers over this powerful novel.”

“Death hovers over this powerful novel.” It’s been far too long since I wrote anything here and I apologise to anyone who might have been wondering what I’ve been up to in the past year and a half. Briefly, like that of most people, my life has been shaped (misshaped?) by Covid-19. Living in Italy, I was among the first to feel the practical effects of the pandemic, with a lockdown that began on 8 March. You can read about my reactions to the first month or so

It’s been far too long since I wrote anything here and I apologise to anyone who might have been wondering what I’ve been up to in the past year and a half. Briefly, like that of most people, my life has been shaped (misshaped?) by Covid-19. Living in Italy, I was among the first to feel the practical effects of the pandemic, with a lockdown that began on 8 March. You can read about my reactions to the first month or so  But the relative freedom brought with it a sense of frustration that many other people have felt, I’ve since discovered, as though the more the restrictions were relaxed the more we were obliged to replace them with our own sense of what was required, and to apply that sense. Will power, in other words, took the place of external coercion, and will power is both a more flexible and a more forgiving master, or so we like to think until the final reckoning is made. Choice is a gift, and a hard gift to manage and a choice that protects others at the cost of one’s own pleasure isn’t always as straightforward as it ought to be. In Sardinia, where we went for ten days in the false security of post-lockdown August, we found deserted beaches but teeming streets, intermittently worn masks and variable social distancing as tourists edged their way along crowded alleys in the Marina district of Cagliari. There was a kind of devil-may-care euphoria and an underlying, constant buzz of anxiety and suspicion that none of this should really be happening. A suspicion that turned out to be well-founded. We left the island on one of the last ferries before a second lockdown was imposed. We left, and remain, unscathed by Covid-19. We were careful, and we were lucky, and we know it.

But the relative freedom brought with it a sense of frustration that many other people have felt, I’ve since discovered, as though the more the restrictions were relaxed the more we were obliged to replace them with our own sense of what was required, and to apply that sense. Will power, in other words, took the place of external coercion, and will power is both a more flexible and a more forgiving master, or so we like to think until the final reckoning is made. Choice is a gift, and a hard gift to manage and a choice that protects others at the cost of one’s own pleasure isn’t always as straightforward as it ought to be. In Sardinia, where we went for ten days in the false security of post-lockdown August, we found deserted beaches but teeming streets, intermittently worn masks and variable social distancing as tourists edged their way along crowded alleys in the Marina district of Cagliari. There was a kind of devil-may-care euphoria and an underlying, constant buzz of anxiety and suspicion that none of this should really be happening. A suspicion that turned out to be well-founded. We left the island on one of the last ferries before a second lockdown was imposed. We left, and remain, unscathed by Covid-19. We were careful, and we were lucky, and we know it. So what have I been reading? I’ve had a whale of a time (forgive me) re-reading Moby Dick after fifty years, reading Pinocchio in Italian, I’m ashamed to say for the first time, and finding a stranger and more wonderful book than I’d ever have imagined. And this was preparation for Edward Carey’s extraordinary novel, both addendum and homage to the Pinocchio story, The Swallowed Man. I discovered, thanks to that always reliable book blog

So what have I been reading? I’ve had a whale of a time (forgive me) re-reading Moby Dick after fifty years, reading Pinocchio in Italian, I’m ashamed to say for the first time, and finding a stranger and more wonderful book than I’d ever have imagined. And this was preparation for Edward Carey’s extraordinary novel, both addendum and homage to the Pinocchio story, The Swallowed Man. I discovered, thanks to that always reliable book blog

… my latest novel,

… my latest novel,  The apartment we’re renting in the Landstrasse district of Vienna is more or less halfway between an immense drum-like tower and the Wittgenstein House. The tower forms part of a reinforced concrete fortress, which we can see looking left from the entrance to our building. It rises in a small park behind a block of social housing that bridges the road and bears the name Kurt-Steyrer-Hof. I thought Kurt Steyrer might be the architect but he turns out to have been a minister of health (with, unusually in these expert-wary days, an actual degree in medicine) and the unsuccessful rival in the presidential elections of 1986 of Kurt Waldheim; he survived Waldheim by a month, dying in 2007, although the building appears to predate this by several decades. The fortress itself, I discover when I walk under the arch of the K-S-H and into the park to look at it more closely, is an almost windowless rectangular building, 187 feet square, unadorned by graffiti, with not one but four round, squat drums rising from a jutting-out tray-like structure to tower above the surrounding trees to a height of 137 feet. It’s the kind of thing an unimaginative child might erect on a beach for the pleasure of seeing it later washed away.